|

p211

[The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was] brought in

by the London and New York banks to enforce [third world] debt repayment and

act as "debt policeman." Public spending for health, education

and welfare in debtor countries was slashed, following IMF orders to ensure

that the banks got timely debt service on their petrodollars. The banks also

brought pressure on the U.S. government to bail them out from the consequences

of their imprudent loans, using taxpayer money and U.S. assets to do it. The

results were austerity measures for Third World countries and taxation for

American workers to provide welfare for the banks.

p214

When new oil reserves were discovered in Mexico in the 1970s, President Jose

Lopez Portillo undertook an impressive modernization and industrialization

program, and Mexico became the most rapidly growing economy in the developing

world. But the prospect of a strong industrial Mexico on the southern border of

the United States was intolerable to certain powerful

Anglo-American interests, who determined to sabotage Mexico's industrialization

by securing rigid repayment of its foreign debt. That was when interest rates

were tripled. Third World loans were particularly vulnerable to this

manipulation, because they were usually subject to floating or variable

interest rates.'

Why did Mexico need to go into debt to foreign

lenders? It had its own oil in abundance. It had accepted development loans

earlier, but it had largely paid them off. The problem

for Mexico was that it was one of those intrepid countries that had declined to

let its national currency float. Mexico's dollar reserves were exhausted by

speculative raids in the 1980s, forcing it to

borrow just to defend the value of the peso. According to Henry Liu, writing in

The Asia Times Mexico's mistake was in keeping its currency freely convertible

into dollars, requiring it to keep enough dollar reserves to buy back the pesos

of anyone wanting to sell. When those reserves ran out, it had to borrow

dollars on the international market just to maintain its currency peg.

In 1982, President Portillo warned of "hidden

foreign interests" that were trying to destabilize Mexico through panic

rumors, causing capital flight out of the country. Speculators

were cashing in their pesos for dollars and depleting the government's dollar

reserves in anticipation that the peso would have to be devalued. In an

attempt to stem the capital flight, the government cracked under the pressure

and did devalue the peso; but while the currency immediately lost 30 percent of

its value, the devastating wave of speculation continued. Mexico was

characterized as a "high-risk country," leading international lenders

to decline to roll over their loans. Caught by peso devaluation, capital

flight, and lender refusal to roll over its debt, the country faced economic

chaos. At the General Assembly of the United Nations, President Portillo called

on the nations of the world to prevent a "regression into the Dark

Ages" precipitated by the unbearably high interest rates of the global

bankers.

In an attempt to stabilize the situation, the

President took the bold move of taking charge of the banks. The Bank of Mexico

and the country's fm-o" private banks were taken over by the governments

with compensation to their private owners. It was the sort of move calculated

to set off alarm bells for the international banking cartel. A global movement to nationalize the

banks could destroy

their whole economic empire. They wanted the banks privatized and under

their control. The U.S. Secretary of State was then George Shultz, a major

player in the 1971 unpegging of the dollar from gold. He responded with a plan

to save the Wall Street banking empire by having the IMF act as debt policeman.

Henry Kissinger's consultancy firm was called in to design the program. The

result, says Engdahl, was "the most concerted organized looting operation

in modern history," carrying "the most onerous debt collection terms

since the Versailles reparations process of the early 1920s," the debt

repayment plan blamed for propelling Germany into World War II.

Mexico's state-owned banks were returned to private

ownership , but they were sold strictly to domestic Mexican purchasers. Not

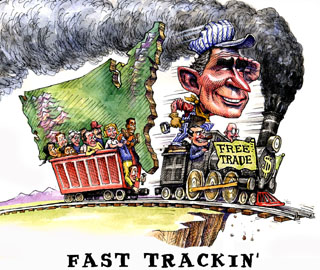

until the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was foreign competition

even partially allowed. Signed by Canada, Mexico and the United States, NAFTA

established a "free-trade" zone in North America to take effect on

January 1, 1994. In entering the agreement, Carlos Salinas, the outgoing

Mexican President, broke with decades of Mexican policy of high tariffs to

protect state-owned industry from competition by U.S. corporations.

By 1994, Mexico had restored its standing with

investors. It had balanced budget, a growth rate of over three percent, and a

stock market that was up five-fold. In February 1995, Jane Ingraham wrote in

The New American that Mexico's fiscal policy was in some respects

"superior and saner than our own wildly spendthrift Washington

circus." Mexico received enormous amounts of foreign investment, after

being singled out as the most promising and safest of Latin American markets.

Investors were therefore shocked and surprised when newly-elected President

Ernesto Zedillo suddenly announced a 13 percent devaluation of the peso, since

there seemed no valid reason for the move. The following day, Zedillo allowed

the formerly managed peso to float freely against the dollar. The peso

immediately plunged by 39 percent.

What was going on? In 1994, the U.S. Congressional

Budget Office Report on NAFTA had diagnosed the peso as "overvalued" by

20 percent. The Mexican government was advised to unpeg the currency and let it

float, allowing it to fall naturally to its "true" level. The theory

was that it would fall by only 20 percent; but that is not what happened.

Speculators pushed the peso down sharply and abruptly, collapsing its value.

The collapse was blamed on the lack of "investor confidence" due to

Mexico's negative trade balance; but as Ingraham observes, investor confidence

was quite high immediately before the collapse. If a negative trade balance is

what sends a currency into massive devaluation and hyperinflation, the U.S.

dollar itself should have been driven there long ago. By 2001, U.S. public and

private debt totaled ten times the debt of all Third World countries combined.

Although the peso's collapse was supposedly

unanticipated, over 4 billion U.S. dollars suddenly and mysteriously left

Mexico in the 20 days before it occurred. Six months later, this money had

twice the Mexican purchasing power it had earlier. Later commentators

maintained that lead investors with inside information precipitated the

stampede out of the peso. The suspicion was that these investors were the same

parties who profited from the Mexican bailout that followed. When Mexico's

banks ran out of dollars to pay off its creditors (which were largely U.S.

banks), the U.S. government stepped in with U.S. tax dollars. The Mexican

bailout was engineered by Robert Rubin, who headed the investment bank Goldman

Sachs before he became U.S. Treasury Secretary. Goldman Sachs was then heavily

invested in short-term dollar-denominated Mexican bonds. The bailout was

arranged the day of Rubin's appointment. The money provided by U.S. taxpayers

did not go to Mexico but went straight into the vaults of Goldman Sachs, Morgan

Stanley, and other big American lenders whose risky loans were on the line.

The late Jude Wanniski was a conservative economist

who was at one time a Wall Street Journal editor and adviser to President

Reagan. He cynically observed of this baker coup:

There was a big party at Morgan Stanley after the

Mexican peso devaluation, people from all over Wall Street came, they drank

champagne and smoked cigars arid congratulated themselves on how they pulled it

off and they made a fortune. These people are pirates, international pirates.

The loot was more than just the profits of gamblers

who had bet the right way. The pirates actually got control of Mexico's banks.

NAFTA rules had already opened the nationalized Mexican banking system to a

number of U.S. banks, with Mexican licenses being granted to 18 big foreign

banks and 16 brokers including Goldman Sachs. But these banks could bring in no

more than 20 percent of the system's total capital, limiting their market share

in loans and securities holdings." By 2004, this

limitation had been removed. All but one of Mexico's major banks had been sold

to foreign banks, which gained total access to the formerly closed Mexican

banking market.

The value of Mexican pesos and Mexican stocks

collapsed together, supposedly because there was a stampede to sell and no one

around to buy; but buyers with ample funds were sitting on the sidelines,

waiting to pick over the devalued stock at bargain basement prices. The result

was a direct transfer of wealth from the local economy to international money

manipulators. The devaluation also precipitated a wave of privatizations (sales

of public assets to private corporations), as the Mexican . government tried to

meet its spiraling debt crisis In a February if article called "Militant

Capitalism," David Peterson blamed the rout on an assault on the peso by

short-sellers. He wrote:

The austerity measures that the U.S. government and

the IMF forced on Mexicans in the aftermath of last winter's assault on the

peso by short-sellers in the foreign exchange markets have been something to

behold. Almost overnight, the Mexican people have had to endure dramatic cuts

in government spending; a sharp hike in regressive sales taxes; at least one

million layoffs (a conservative estimate); a spike in interest rates so

pronounced as to render their debts unserviceable ... a collapse in consumer

spending on the order of 25 percent by mid-year; and, in brief, a 10.5 percent

contraction in overall economic activity during the second quarter, with more

of the same sure to follow.

By 1995, Mexico's foreign debt was more than twice

the country's total debt payment for the previous century and a half.

Per-capita income had fallen by almost a third from a year earlier, and Mexican

purchasing power had fallen by well over 50 percent." Mexico was propelled

into a crippling national depression that has lasted for over a decade. As in

the U.S. depression of the 1930s, the actual value of Mexican businesses and

assets did not change during this speculator-induced crisis. What changed was

simply that currency had been sucked out of the economy by investors stampeding

to get out of the Mexican stock market, leaving insufficient money in

circulation to pay workers, buy raw materials, finance loans, and operate the

country. It was further evidence that when short-selling is allowed, currencies

are driven into hyperinflation not by the market mechanism of "supply and

demand" but by the concerted action of currency speculators.

|