|

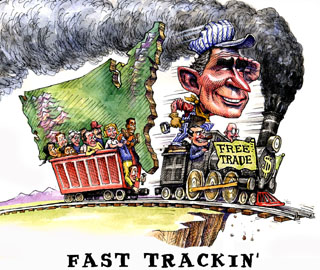

After the crushing victory of Morales’ MAS with 53.7% of the votes, Bolivia has become the newest

member of the growing ‘‘axis of good’‘ in Latin America, and the US’s latest headache.

Morales’ victory represents the continued loss of control of the US over Latin American governments,

including in Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. But it also strengthens

the anti-imperialist pole within the continent, as Morales joins the ranks of the two other presidents, Fidel Castro in Cuba and Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, who are willing to openly

oppose US imperialism.

In response to Morales’ victory, Cuban President Fidel Castro and Richard Alacorn, president

of the National Assembly of People’s Power of Cuba, sent a letter to Morales stating: “With your victory, a new

history is born, the history of the emancipation of the peoples whom colonialism and racism wanted to crush and wipe out.

Finally, after half a millennium of genocide, they come to power with you.” Before

being sworn in, Morales visited Cuba on December 30, at the invitation of Castro. Morales described

the encounter as a “meeting of two revolutions”. This was his first destination as president-elect, rather than

Washington, the common practice for previous Bolivian presidents. The close public relationship between these two leaders,

together with Chavez in Venezuela, has been the cause of much concern for the US administration. During

the election campaign, the US, along with the media and leading right-wing presidential candidate Jorge “Tuto”

Quiroga, attempted to smear Morales by claiming Chavez was funding his campaign and interfering in Bolivian domestic issues

in order to spread his influence in the “axis of evil”.

During Morales’ visit to Venezuela, his second stop in a

world tour that included Spain, South Africa, Iran, Brazil, Argentina and China, he said Bolivia was joining “the

anti-neo-liberal and anti-imperialist struggle of the Latin American peoples”. Chavez responded to the US’s claims by stating

that “ours is the axis of good, that of the peaceful development of the peoples. The other one, which threatens, invades

and murders, is the axis of Washington and its allies — that is the real axis of evil.” As a concrete sign of what such an axis of good will mean, Morales signed an 11-point agreement with Cuba. Cuba will provide 50,000

free eye operations a year for Bolivians, 5000 scholarships for students to study medicine in Cuba and assistance in a united

campaign to eradicate illiteracy in Bolivia — South America’s poorest country — within two years. Venezuela agreed to meet all of

Bolivia’s diesel fuel needs with 150,000 barrels of diesel each month, worth US$180 million

a year, in exchange for agricultural products. Chavez also affirmed that Venezuela would donate US$30 million

for social projects in Bolivia..

As well as receiving support from other governments, many of South America’s social movements, which have been

invited to La Paz for Morales’ official swearing in on January 22, also passed on their solidarity. From Ecuador, Salvador Quipse, leader

and parliamentary deputy for the party Pachakuti, pointed out that this victory was “a very important step that will

politically and socially strengthen the indigenous peoples of Latin America”.

The impact of Morales’ victory is particularly evident in Peru, where ex-military figure

and nationalist presidential candidate Ollanta Humala now leads the polls, as support for him grows among Peru’s poor, many of

whom are indigenous and coca growers.

Unsurprisingly, the Bush administration’s comments went against the tide of support, reflecting

that the US was the principal loser in this election and will be the principal danger for

the Morales government. US secretary of state Condoleezza Rice commented the day after

the elections that the US would “observe the behaviour of the Bolivian government

to determine the course of relationships”.

With the first coca-growing president in the world declaring his intention to nationalise Bolivia’s gas reserves in

the heart of growing continental rebellion against neoliberalism, there is no doubt that relations between Bolivia and the US, particularly over the

issues of gas and drugs, will be contentious. The strengthening of the more radical, anti-imperialist elements within the

growing sea of governments that have opted, to varying degrees, to pursue a line of autonomy from the US, will also be seen as

a big danger. Expressing the attitude of at least some in Washington, Otto Reich, former US secretary for Latin American affairs,

wrote, “Hopefully Evo Morales will not put into practice what he has said in his campaign”, adding menacingly

that this “would be really bad for the future of Bolivia. The world can live without Bolivia, but Bolivia cannot live without the

world.” The reality is that more and more people across the continent are

seeing that they can live without US interference. That is why the newly established US military

base on the Bolivia-Paraguay border, previous comments by US government officials and departments about the threats of “populism”

increasing the likelihood of the “disintegration” of the “failed state” of Bolivia, as well as the

recent destruction of anti-aircraft missiles — a demand of the US that outgoing president Eduardo Rodriguez acquiesced

to in October last year — indicate a possible pretext for US intervention into Bolivia. This should be a of concern

to those around the world that are struggling for an alternative to imperialism and neoliberalism. As Castro and Alarcon declared

in their letter to Morales: “You and your people have before you new and great challenges. It is necessary that you

be accompanied, from right now, by the full solidarity of the entire world.”

|